“Great minds discuss ideas. Average minds discuss events. Small minds discuss people.”

— Paraphrased from Henry Thomas Buckle

Before we can have any meaningful discussion—especially about ideas—we need to agree on how we’ll engage. That doesn’t mean we have to agree on everything. In fact, we may already disagree. But without some ground rules, we’re just talking past each other.

The Ground Rules

- Truth exists: For any given topic at any given time, there is one objective truth. That truth may be known by one of us, both, or neither.

- Strategy allows variance: If we’re debating how best to achieve a shared goal (e.g., improving health, winning an election), there might be more than one valid path. The disagreement then is about efficacy.

- Subjective views are not debatable: If we agree that something is a matter of taste or preference, there’s no point in arguing, just a chance to understand each other better.

- Philosophical questions live in the gray: These often blend subjective and objective elements. If we want a fruitful discussion, we’ll need to first agree on the level of objectivity involved.

- Agreeing on the nature of the defining the disagreement typeng in, we should first ask: Are we debating fact, preference, or method?

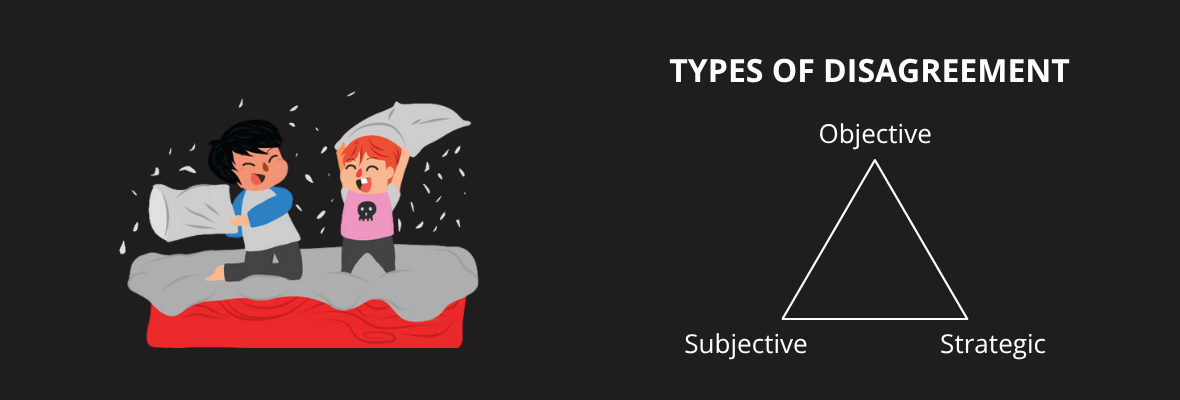

Without clarity on what we’re actually disagreeing about, we risk going in circles. So when a disagreement arises, our first task is to define the type of disagreement.

Types of Disagreement

Subjective:

You say vanilla is better than strawberry flavor. I say chocolate is better than vanilla.

At that point, we’re talking preferences. There’s nothing to prove. We shake hands and move on.

At that point, we’re talking preferences. There’s nothing to prove. We shake hands and move on.

Objective:

You say vanilla ice cream is better. I say chocolate is healthier because of antioxidants and mood-boosting compounds.

Now we’ve shifted into a claim that can be tested or supported with evidence. Even if you counter that vanilla makes you feel better, the question then becomes: are we measuring inherent properties or personal effects?

Strategic:

You and I both want better health. You favor intermittent fasting with calisthenics. I prefer traditional strength training with a macro-controlled diet.

Here, we’re aligned on the goal but not the method. Strategy disagreements are common, and usually require time, experimentation, or data to settle. This is where most debates on politics, policy, and systems tend to fall.

Here, we’re aligned on the goal but not the method. Strategy disagreements are common, and usually require time, experimentation, or data to settle. This is where most debates on politics, policy, and systems tend to fall.

So What About Religion?

Let’s not pretend this doesn’t come up. But before diving into theology or metaphysics, let’s ask:

- Are we discussing truth claims?

- Personal experiences?

- Cultural practices?

- Strategy for living a good life?

Each of those lenses offers a different kind of conversation. And often, the real conflict comes from mistaking one type for another.

Final Thought:

Disagreement isn’t the problem. Confusion about what we’re disagreeing on is.

When we start by identifying the nature of the disagreement—objective, subjective, or strategic- we set ourselves up for clarity, respect, and maybe even progress. And when that’s not possible?

Agree to disagree—with grace and good faith.

What do you think? Do you agree, disagree, or want to add a fourth category?

Reader Interactions